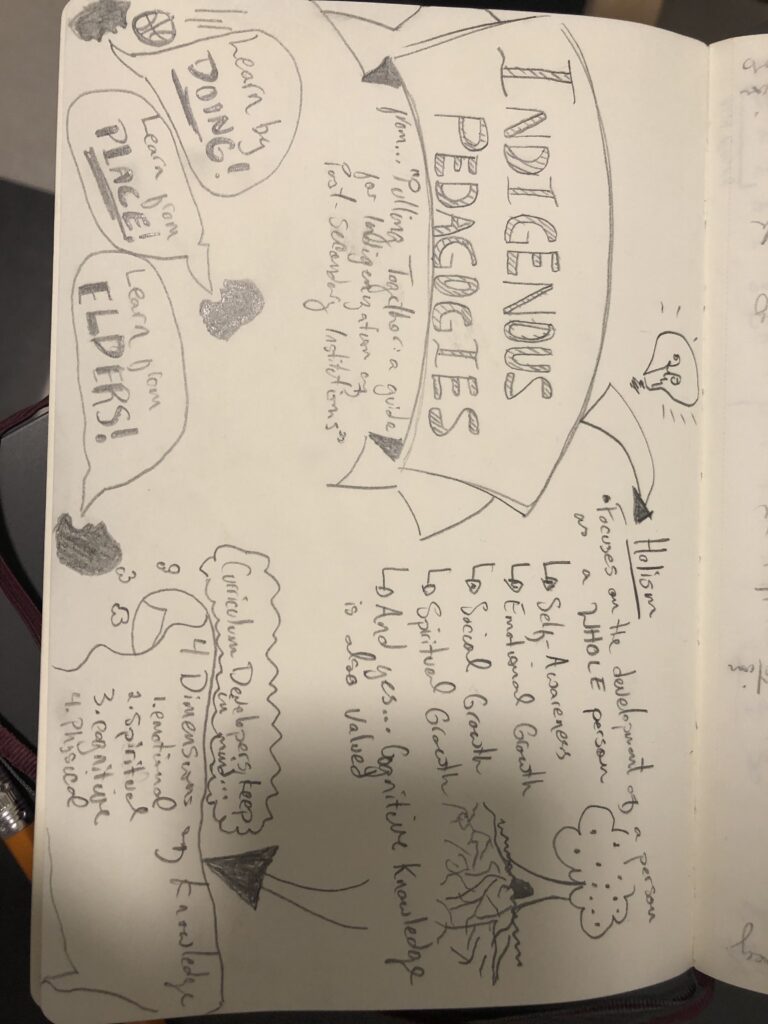

Throughout the last months I have been writing diaristic accounts. Sometimes fictional, sometimes autobiographical, I hoped that through writing I could learn more about the process and to sufficiently honour it by blurring the lines between the working and the work. So far it’s felt like a success–documenting the starts and stops; the doubt and the elation; watching the fervour of my motivation wax and wane has brought me closer to the book I have in mind, one that is identical to the narrator’s: equally a book of poems as it is about writing a book of poems. However, while progress has been made, one key question remains: how will these prosaic fragments fit with the poems? How will they interact? Currently, I see three possible arrangements:

1. The collection of poems are included in a separate section. After a first section of meditative prose, lyrical fragments, and a loose, not entirely linear plot, the poems are presented in full, as part of the narrative. This could be the narrator sending his collection out to publishers, reviewing one last time everything he’s written; or it could be looking over the shoulder of a friend who he’d asked to read them–it could be anything. The point is, the poems would be the work of the narrator, not the author. And I’m not sure how I feel about this–turning the poems into fiction and my poetry book into a novel.

2. The poems and the prose fragments appear one after the other; although, of course, there will be more fragments than poems. In this iteration, the poems and the fragments are both the author’s, and are treated rather equally. A few things about this version bother me. First, they aren’t equal, at least not in their design. The poems are very much finished products, completed over the course of months and in some cases years, while the fragments are meant to be what the author does when he isn’t “writing.” Secondly, I’d like it if the poems and fragments were somewhat in conversation; like, maybe the prose is a kind of time keeping of the poems? This version just seems a little haphazard to me, lacking intent. But also maybe that’s okay?

3. A series of prose fragments follow each poems (one fragment per page) but are attached to the poem by the use of superscripts. The relationship between fragment and poem would mimic that of footnotes, though the purpose and the page layout would differ greatly. This and the first option are the ones I’m leaning most toward. I just fear the superscript will rob some of the aesthetics from the poem! I don’t want that, but I do want coherence between the two forms. A conundrum.

Below is a poem for the book, so that you can have a slightly fuller sense of the tone of the work. I was going to include the superscripts with corresponding prose fragments from the inquiry posts, but the little numbers hovering above the letter were too distracting! (P.S. The poem is in couplets. I just couldn’t figure out how to leave space between each line on the blog…)

Once, It Happened A Boy

It was in the liquid shade of a yucca tree

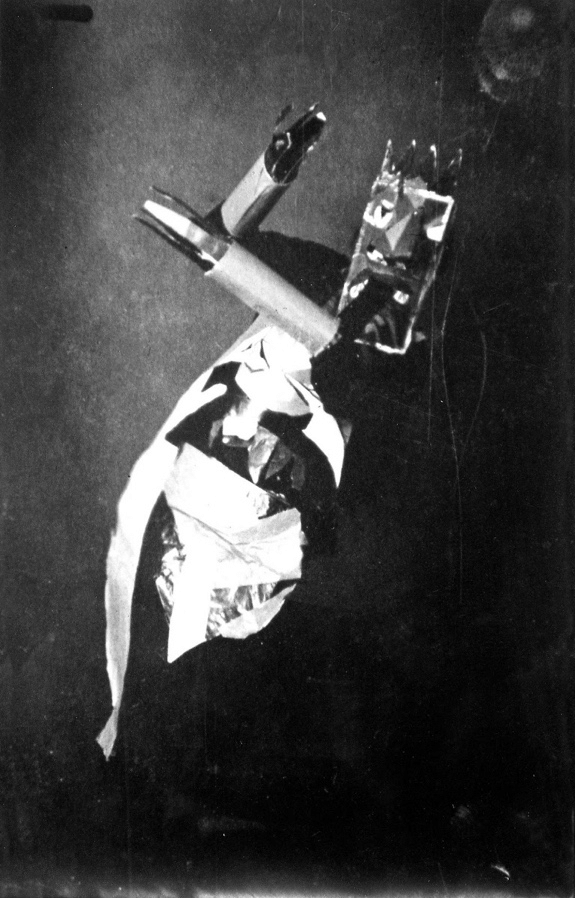

each quivering line of the boy’s body broke

to silver, then leaf—

sharp contours assailing angled light

like a flotilla cutting waves, a vascular wing

macheteying

towards this clumsy shimmering

pool of soil

cradling my reflection like its own.

Once, it happened a boy.

It happened under over-ripened suns

at the pace of a fouling room—

his broke away from mine, left me

in this frame of mud and stone a canvas teetering

at the sharp edge of a new leaf, witness

to my own unfurling.

When I reached for him I dug out fists full

of wet hair, long stringy clumps flecked with ash,

gnats, tiny globular pellets like furry teeth

spat up from a pentimento world.

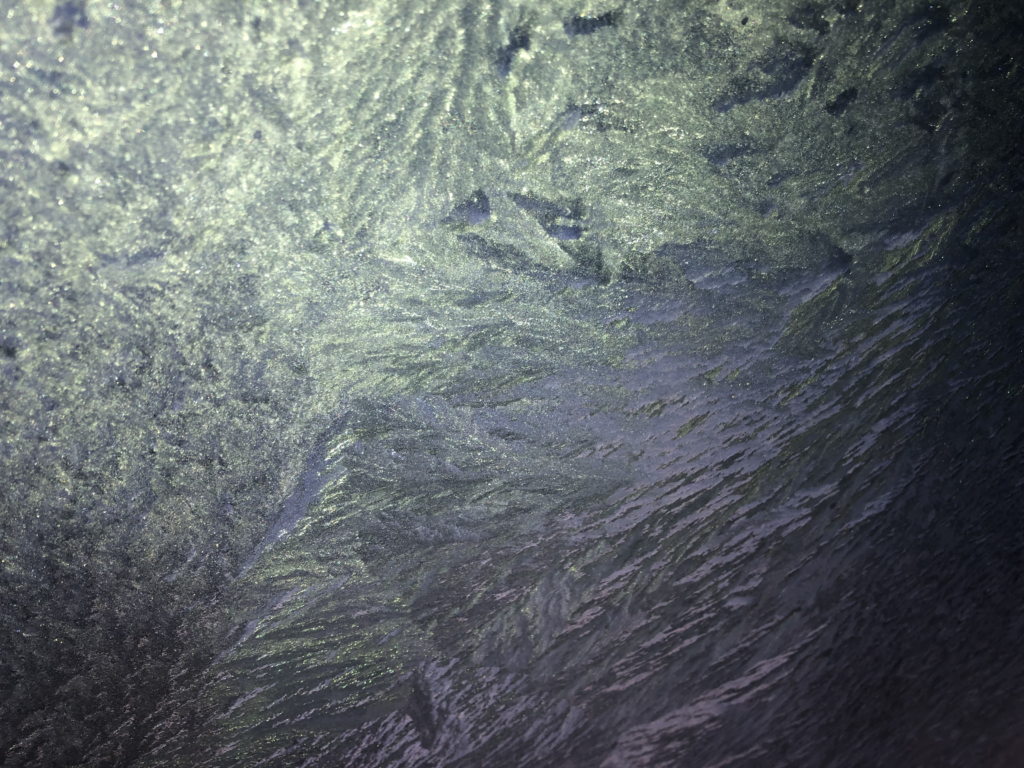

Crystal coronets of violet, indigo, cochineal

painted rings around my lips as I stayed up drinking

back the flowers of the yucca shade,

cupping my hands, our hands, to the blurring canvas

remembering the way an oil slick recalls the earth

the tilt of an August sky that held its blue

forever—once,

it happened a boy was made

the promise to be held the same: forever

in a breath of summer carried over coning lupine;

in a wonton splay of light

netting argosies

of dust, each fleck buoying a life

intent on surfacing,

no matter how or when or what

conditions of the surface

it happens—just that it happens,

the beauty you possess now on earth is seen, bright.

So unlike anything else.

First published in Funicular Magazine, issue 10, 2022.

A version of another poem published in the same issue is available here.