Love. They said to trust your heart. Everyday in every corner a little man—almost always a man—sang Love is all you need, and the parents bought tickets and waved their cellphones with no connection in the air. Then we found out the singing man was an abuser. Yet, somehow his message lost no validity—love was still the answer, still all you needed, and it was still as simple as just choosing it. Everybody had that single tool that could fix the world. And the tool, we were made to believe, was as intuitive as a hammer.

Happiness. They said to follow your passions; do what you love and you’ll be happy. And everybody wanted so much to just be happy! It should be the simplest thing, they figured, the most natural thing, as if we skipped out of the womb smiling. Why can’t you just be happy?

The chronic scepticism that whatever I’m doing I should be doing more passionately.

Does anybody else feel this?

In university it was trendy to take a scientific approach to literature. We said things like “neuromoduality” and “affectual cybernetics” in our classes; we discussed the statocysts of jellyfish in seminars on Modernism. I was constantly taking notes, documenting a growing sense of illumination to my own proprioception, like the tentacles of my mind were stretching out, uncurling, unravelling. We sprawled on the campus grass during another heat dome, passing homemade horchata between a small cohort of us and challenged our otolithic instincts that craved a balanced plot. The new literature—one whose intertextuality could keep up with the intertextuality of life, the porosity of it—would be definitionally unbalanced, we decided, though Carlos was the only one writing it. Excerpts of the erotic play he was writing were published in the university’s literary magazine, The Pulp, which one of us always had a copy of on hand. The idea was to use neuroscientific research to stake a claim for literature in a numbers-obsessed future. Like Benjamin arguing the phylogenic basis for human mimetic capability in his essays on photography we talked about metaphor being the basis of human reasoning, that concepts like future and past were developmentally inferred through the embodied experience of movement and speed; happy and sad emotional concepts that still contain their embodied antecedent of high and low; or the classic, possibly oldest living metaphor of understanding as to see. By uncovering a neuro-biological dependence on processes more typical of art than of computation we expected to prove something.

That summer, not far from where we live now, an entire town burst into flames from the heat. Temperatures soared higher than they’ve ever been in Vegas or Miami, and this was Canada. In the house we were living in, one of the tenants’ cats was sick with heat stroke, so he took a pillow from his bed and slept with her on the cool cement floor of the basement. He said he didn’t care that there was a break in months earlier; that he knew the spiders were awful in that house, and he knew about the centipedes. In the morning we heard nothing about bugs or burglaries; what we woke to was a kind of widening, a stretching of a single vowel coming from deep within the house. In the night the cat had crawled behind some pipes into an exterior wall, her moaning reverberating through the floorboards, through the walls. A note was slipped under everybody’s doors.

CAT STUCK DON’T USE WATER

Did he think the sound of the water running through the pipes would scare her further into the wall? Maybe he was afraid of the heat from the pipes scolding her?

I told this to a friend I was having coffee with this morning after she finished telling me about a deadly green paint fashionable in the Victorian Era called Scheele’s green, which was created by combining copper with arsenic. The result, she said, was a hue that was cheaply produced and that accurately mimicked the vivid saturation of the vegetal greens found in nature, the colour of fiddleheads and haircap moss. Dresses, waistcoats, shoes, gloves, trousers, and jewelry all conveyed the beauty and tranquility of the forest, which, usually at the price of a rash or the occasional oozing sore, city-dwellers went mad for; but when they dressed their walls in it people began mysteriously dying. Still, even after the effects were known, people continued buying it. “What do you think is the Scheele’s green of our time?” I asked.

“Free market fundamentalism,” she said. “It’s always been.”

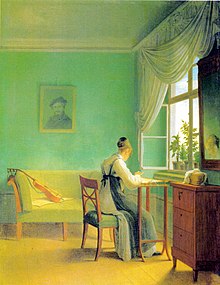

EMBROIDERY WOMAN, GEORG FRIEDRICH KERSTING, 1817.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.