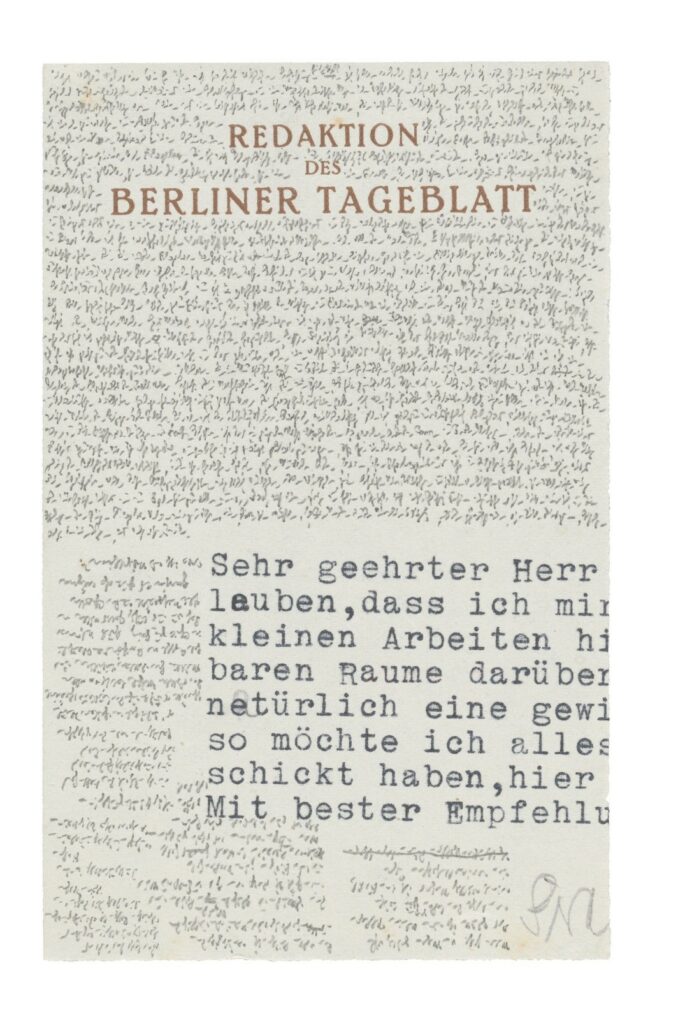

In a single sentence, literary critic Walter Benjamin attempts to catch the essence of Robert Walser’s entire gaggle of fictional characters. They have all been healed, he writes. A prescribed history of suffering may be read in this, as it often has been—the conflicts, the climaxes, and the resolutions all behind them, so they step weightlessly in line with the distinctive airy innocence of the author’s narrative voice. What’s strangely coincidental is that in the same year that Benjamin writes of Walter’s characters being healed, Robert Walser himself is diagnosed with catatonic schizophrenia. His handwriting shrinks to a diminutive Sütterlin hand, each letter barely measuring a millimetre in height, his stories now being written on the back of receipts, business cards, scraps of ephemera. What the size of his writing says about his state of mind I don’t know; nor do I know anything about the Christmas day photographs of the author dead in the snowy field behind the Herisau asylum—his image eerily reminiscent of an image featured in his first novel, written nearly fifty years earlier. Benjamin’s achievement in his summarizing sentence rests in what it doesn’t do—that is, it resists the deadening effect of description. Healed—from what? How? To whose expense? The word gives very little, yet there’s something unmistakably true about it—not in light of Walser’s presumed mental instability, which would render the sentence uncharacteristically banal and even condescending—but in reference to the mythic wound that gapes between the author and his art. Walser’s narrative “I” is instrumental to the content of his fictions, though only rarely do they become autofictions; instead, it seems like Walser’s characters have overcome the existential plight of trying to be what they aren’t—namely, people. If convalescent is the mood of Walser’s writing, as Benjamin claims, it is the cosmic convalescence of creation, of being from non-being.

“We don’t need to see anything out of the ordinary,” Walser writes as himself/narrator at the end of “A Little Ramble.” “We already see so much.”

The suite I was renting was in a little rat-infested stone castle that had been converted into micro-lofts, its smell the damp musk of mold and incense burned in the crystal shop on the ground floor, where I worked. After emptying the till and shutting off the lights in the crystal shop, I’d made it a routine to take a seat beside the rose quartz, delicately placing my palms over its closed lids until the thread of a poem would appear, which didn’t usually happen but sometimes did so I had to keep up the ritual. Mostly I ended up writing about other stuff—about what I was reading, my job, neighbourhood people, Leo—which wasn’t really what I was writing, but helped to unearth the person who would write what I wanted to write, the poems. My hope was that I could learn to be more like the person who would write these poems, the author of the small collection I’d begun calling Grace Notes.

How being someone else was always the easier task. Why did people insist you must be yourself, while simultaneously claiming You can be anything!? Where did this thinking come from—this anxiety of self-dispossession, everybody overly-eager to claim their plans before anybody else did, as if the world suffered a scarcity of originality?

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.