I quit the essay on Sophie Tauber which I’d spent most of last year writing. The document had become too porous, too much about me—it read hesitantly, quite unsure of itself; I would feel sorry any time I looked at it, recognizing fits of passion and the long periods of demurral I experienced while writing. It seemed accidentally paced to the changing rhythms of my own interiority. But what troubled me most was an insecurity that had developed early on around what authority I had in respect to the artist’s work, what right I had to write about it, to have a voice, which was an insecurity about writing in general. This ballooned into a dominating presence, forcing the writing into the margins as my doubts inflated and the essay died.

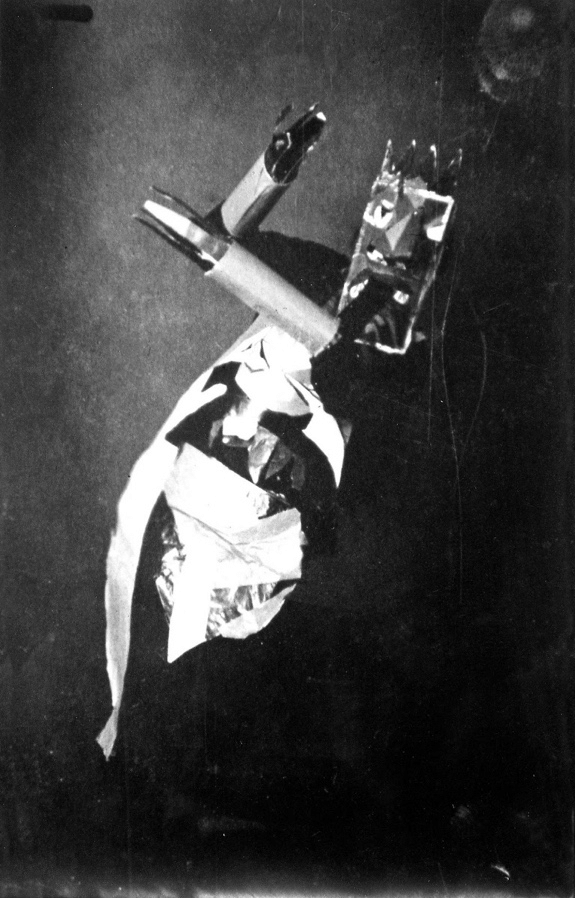

On my desk, paper-clipped to a page photocopied from German writer Hugo Ball’s diary is one of my favourite Dada photographs. It’s of Sophie dancing at the opening of Zürich’s Gallerie Dada, circa 1917. A passage of the diary is highlighted: “The lines of her body break, every gesture decomposes into a hundred precise, angular, incisive movements.”

Yesterday, washing jars in the kitchen sink, the end of my sleeve caught some soapy dishwater which made my sweater feel weighted around the wrists, cumbersome, because of its sudden wetness.

How the smallest things send my lines askew.

From the Sophie Tauber essay:

Fathers of dictation speak of muses visiting their desks in moments of inspiration, which is kind of like the cosmic flare that lights up on your phone screen any time you press your finger to the tender spot where the glass is cracked. Glow of ethereal aura, you write down.

There is a version in my mind of Clarice Lispector’s Complete Stories in which a single line is all that exists, among the 627 otherwise blank pages:

I said your name so many times until the name changed into a name I liked more: Hermendargdo…

T.S. Elliot wrote “you are the music while the music lasts” while tripping to Viagra Boys.

When did life become falling through an elevator shaft of open windows? When was this what you started asking for?

On the edge of beatific imminence, you write down.

What was I even doing?

Thinking about Annie Ernaux’s Passion Simple, the unnamed narrator’s compulsive doubting, the elation she knows can’t last but wants so bad to trust, to just feel, fully, without the dread of its loss. There’s tragedy in this—not so much in the affair, or even in the well-lamented caprice of love, but in the fear, which gets in the way of ever really experiencing it. “I would count the number of times we had made love. I felt that each time something new had been added to our relationship but that somehow this very accumulation of touching and pleasure would eventually draw us apart. We were burning up a capital of desire. What we gained in physical intensity we lost in time.”

How the accumulation of touching and pleasure comes so close to the amassing of words. Each fragmented interaction pulling the reader closer, closer. I’m not surprised, reading a collection of letters sent in to Annie after the book’s publication while I’m waiting in the atrium for R—— to arrive from work, by the anxieties her readers experienced after finishing it. Worried whether the author drinks coffee or tea; whether she’s at the table now, or if an errand required her to leave the house early; perhaps she’s in traffic—would she whistle? What does she play on the radio? The reader feels they are owed something, a destination; the book: a passage through an artery of the author’s life.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.